Filling a Critical Gap in the Gut

Discovery

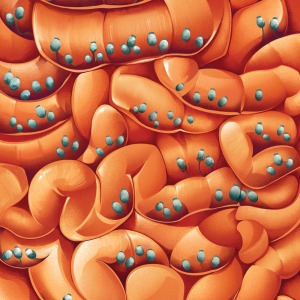

An important discovery positions fungi as a missing part of research on how the gut biome influences health.

Has a fungus ever changed your mind? The answer could be yes if you’ve had a particularly compelling culinary or psychedelic experience. But Dr. Iliyan Iliev has found evidence that the mammalian brain may also be influenced by the fungal species that call our digestive tract home.

Last year, Dr. Iliev’s team at Weill Cornell Medicine demonstrated that the transplantation of a customized collection of fungal species into the intestines of lab mice meaningfully increased the time those animals spent socializing with other mice relative to control animals. This remarkable finding highlights just one of many links that his group has uncovered between gut fungal communities and their animal hosts, including a role in diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and cancer.

To be sure, Dr. Iliev’s work on fungi is changing minds in the scientific community. The past 20 years have seen an explosion of research into the gut microbiome — the vast, complex community of microorganisms residing within the intestine. These studies have revealed extensive interplay between these microbes and their hosts in both healthy individuals and those with chronic diseases, but have offered only a partial picture of the microbiome.

“The study of commensal communities has largely focused on bacteria,” says Dr. Tobias Hohl, an immunologist specializing in fungal disorders at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. “I think Iliyan’s work has been at the forefront of bringing appreciation to the fact that nonbacterial constituents are equally important.” And although fungal DNA is estimated to represent just 0.1% of the gut microbiome, the data increasingly suggest that their influence rivals that of their more abundant bacterial neighbors.

Influencing Inflammation

Dr. Iliev’s gateway into this field was his early research into IBD, a condition in which patients experience severe inflammation that progressively damages the intestinal lining. As a postdoctoral fellow at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, he was lead author on a seminal 2012 Science paper demonstrating the physiological importance of interactions between gut fungi and host cells in IBD.

Specifically, this study showed that a protein called Dectin-1 enables immune cells to recognize and respond to gut fungi in mice. Without this protein, mice became susceptible to intestinal inflammation and subsequent fungal overgrowth, and Dr. Iliev and colleagues found that people with mutations in the gene encoding Dectin-1 likewise tended to develop a severe form of IBD.

This paved the way for a deeper dive into the function of this fungal ecosystem. “From there, I started actually coming up with the good questions,” jokes Dr. Iliev. Since joining Weill Cornell Medicine in 2015, he and his team have made substantial headway in understanding how seemingly subtle differences in the gut fungal communities within different individuals affect the risk and severity of IBD.

Part of this community is established at or shortly after birth. These are later joined by other species that we pick up from our environment or food we eat. Some are benign or beneficial, while others are pathogens that undermine their hosts. Dr. Iliev points out that these differences transcend the species level. “Different patients actually carry different strains of the same species,” he says. “Some patients harbor strains that, if they develop a disease, can probably contribute to its severity.”

But as Dr. Iliev’s work has demonstrated, these outcomes are also shaped by the host immune response to these species and strains. His lab has now explored these interactions in detail, looking specifically at the antibodies that mice and humans generate in response to gut fungi. Their results showed that these antibodies act as a check against uncontrolled growth, maintaining a critical equilibrium in healthy individuals. “It’s kind of a ‘gut vaccination’ which, in conjunction with the innate immune response, ensures that healthy humans don’t get systemic fungal infections,” Dr. Iliev says.

Candida albicans has proven to be a particularly important target for this antibody response. This fungal species can exist in a harmless “commensal” state that lives in peace with its host or as a damaging pathogen. Dr. Iliev’s team learned that in healthy individuals, the immune system can distinguish between these two states by generating antibodies within the gut that selectively bind and neutralize the strand-like structures known as hyphae that are formed specifically by pathogenic forms of C. albicans.

His group has also uncovered biological signatures that distinguish harmful subtypes of C. albicans by profiling the fungal microbiomes of IBD patients. When these “bad” strains were transferred to a mouse model of IBD, they consistently accelerated disease progression. Dr. Hohl sees this work as a particularly important accomplishment for Dr. Iliev’s lab, saying, “He is leading the charge in starting to identify important fungal strain characteristics that are associated with disease severity for IBD.”

Beyond the Bowel

But IBD is only the beginning — Dr. Iliev’s research has also uncovered strong evidence linking fungi to various cancers. In a recent collaboration with researchers at Duke University and Dr. Steven Lipkin at Weill Cornell Medicine, his team identified traces of fungal DNA present in tumor samples collected as part of The Cancer Genome Atlas — a vast sequencing dataset derived from numerous patient biopsies obtained from cancers in virtually every tissue of the body.

“The upshot is that tumors of the oral and gastrointestinal tract, such as head and neck cancer, stomach cancer and colon cancer — plus lung and breast tumors — actually have tiny amounts of fungal DNA associated with them,” says Dr. Iliev. Once again, Candida proved to be an important predictor of trouble, particularly in tumors affecting the stomach or colon. Patients with Candida-positive tumors tended to die sooner, and colon tumors associated with these fungal signatures tended to be more aggressive and prone to metastatic growth.

His team’s recent discovery of the behavioral influence of gut fungi proved to be an even bigger surprise. Their initial goal was to test how transplanted gut fungi affect the function of the intestinal wall in mice. The scientists initially monitored the behavior of transplant recipient animals to detect indications of sickness, but soon recognized a distinct pattern of increased social activity in mice dosed with a specific subset of microbes. Closer analysis revealed that these fungi were stimulating immune cells to release a signaling protein known as interleukin-17 into the bloodstream. They found that this protein acted on certain neurons to influence social behavior, suggesting a direct link between the gut fungal microbiome and immune responses that can subsequently modulate brain function.

The identification of putative links between gut fungi and health also creates new opportunities for treatment. A multicenter clinical trial has already provided evidence that “fecal microbiome transplantation” (FMT) from healthy donors can treat IBD in some patients. Iliev’s team found that patients who recovered after transplantation experienced a marked decrease in pathogenic Candida species in their intestine, and this resulted in reduced inflammation. “A lot of those patients who benefited had detectible Candida expansion before FMT, and it decreased after therapy,” he says.

Collaboration has always been a core component of Dr. Iliev’s work, and he is now working with Drs. Randy Longman and Ellen Scherl at Weill Cornell Medicine to translate his team’s findings into the clinics. He also credits Drs. David Artis, Gregory Sonnenberg, Chun-Jun Guo and Julie Blander — plus the team in his own lab — for help in characterizing mucosal immunity within the gut.

But considerable work remains, and Dr. Iliev is keen to learn more about the commensal role of gut fungi and how they support their hosts’ health. Furthermore, as just one component of the larger microbiome community, it is unclear how these fungi collaborate or compete with their microbial colleagues. Dr. Kathy McCoy, a specialist in the bacterial microbiome at the University of Calgary, praises Dr. Iliev’s work for spotlighting a long-overlooked component of the gut ecosystem, and is keen to learn how their interests overlap. “We would be incredibly naïve to think that these different components of the microbiome work alone,” she says.

Summer 2023 Front to Back

-

From the Dean

Message from the Dean

As Weill Cornell Medicine marks the 125th year since its founding, it is striking to reflect upon how our values have endured. -

Features

Window Into the Future

An ambitious research program could hold clues to improving the health of women and their children across their lifespans. -

Features

Caught on Camera

Recordings made in Dr. Simon Scheuring’s lab reveal how elusive molecules embedded in cell membranes get their jobs done — for good and ill. -

Features

Risks and Rewards

Alumnus Dr. Anthony Fauci (M.D. ’66) joins Dr. Jay Varma in a candid conversation about the future of public health and more. -

Notable

Two Landmark Anniversaries

Weill Cornell Medicine is celebrating more than a century of excellence in medical education, scientific discovery and patient care, commemorating 125 years since its founding. -

Notable

Honoring Diversity

In a celebration of Weill Cornell Medicine’s commitment to fostering diversity, equity and inclusion in academic medicine, the institution honored nearly a dozen faculty, students and staff. -

Notable

Overheard

Weill Cornell Medicine faculty members are leading the conversation about important health issues across the country and around the world. -

Notable

News Briefs

Notable faculty appointments, honors, awards and more — from around campus and beyond. -

Notable

Dateline

The Salzburg-Cornell Seminars, now part of the Open Medical Institute (OMI), celebrates 30 years of knowledge-sharing, having served more than 26,000 fellows from 130 countries. -

Grand Rounds

There Is Hope

How immunotherapy offered a new lease on life -

Grand Rounds

Medical School, Minus the Debt

Weill Cornell Medicine’s debt-reduction program. -

Grand Rounds

News Briefs

The latest on teaching, learning and patient-centered care. -

Discovery

Filling a Critical Gap in the Gut

An important discovery positions fungi as a missing part of research on how the gut biome influences health. -

Discovery

New Clues to Coma Recovery

Delays in regaining consciousness may serve a purpose: protecting the brain from oxygen deprivation. -

Discovery

Findings

The latest advances in faculty research, published in the world’s leading journals. -

Alumni

Profiles

Forging critical connections to move research from the bench to the bedside, our alumni are making an impact. -

Alumni

Notes

What’s new with you? Keep your classmates up to date on all your latest achievements with an Alumni Note. -

Alumni

In Memoriam

Marking the passing of our faculty and alumni. -

Alumni

Moments

Marking celebratory events in the lives of our students, including Match Day and Graduation. -

Second Opinion

Nurturing Well-Being

How can the health-care workforce recover from pandemic burnout? -

Exchange

High-Risk, High-Reward

Two enterprising scientists discuss how the ecosystem for innovation at Weill Cornell Medicine provides the support entrepreneurial faculty and students need to turn their promising research into commercially viable drugs and other treatments. -

Muse

In the Flow

Dr. Navarro Millán is a rheumatologist, clinical investigator and multi-instrumentalist. -

Spotlight

Making Health Care Affordable and Equitable

Dr. Cheryl Pegus (M.D. ’88) is a cardiologist working in health-care businesses on new products to meet consumer needs, enhance health equity and improve health outcomes.