Weill Cornell Medicine is rich in partnerships and affiliations, from our hospital partner NewYork-Presbyterian, to close working relationships with neighbors Memorial Sloan Kettering, The Rockefeller University and Hospital for Special Surgery — and we of course are part of Cornell University, and have locations overseas. How might these relationships evolve in the coming years?

The opportunities for tightening collaborative relationships is one of the things that really excited me about Weill Cornell Medicine. We have amazing opportunities to think about how we bring together some of the assets of these different partnerships to make us all better, to do more interesting research, to potentially come up with new care ideas, and to educate in a more collaborative, diverse way.

Part of my role will be to figure out how we do more together. I’m a huge believer that doing it together is way better and more effective and likely creates way better outcomes than people trying to do things on their own. I’m particularly excited about the relationship with Cornell Tech and seeing how we can strengthen relationships between what I’ll call the data sciences, engineering and medicine.

As for our overseas partnerships, medical centers in the United States have a global, social responsibility. We are very fortunate to have resources and investments in our academic health systems that are different than in much of the world. The major diseases of the U.S. are the major diseases of the globe, and so we ought to be looking for how we can all learn from each other and solve problems from a global perspective.

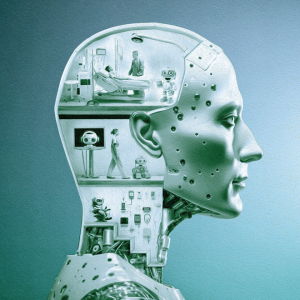

You have a strong interest in artificial intelligence (AI), computational work, and their intersections with medicine. It sounds like you have potentially a lot of ideas about how we might be able to harness that technology.

There are few things in medicine today that excite me more than the potential of discovery science — especially advanced computation, which includes AI and machine learning in health care — to improve the care we already provide, to facilitate breakthroughs in our treatment of disease, and even to create entirely new ways of thinking about medicine. The tools of data science, which includes things like AI, are really where the boundaries of medicine are going to be pushed, and where I predict enormous growth. Whether you’re talking about how you apply AI to discovery, to preventing illness, taking care of patients or as an educational tool, I think that’s all coming and I’m really excited about it. Weill Cornell Medicine has some of the key pieces, including a great parent university with a great engineering school and a president who’s a computer scientist. This is an awesome opportunity to think about how we support and connect all those pieces.

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) is something that we’ve made substantial investments in that have shifted our culture quite a bit. Can you talk a little bit about why DEI is integral to academic medicine and how we can sustain and expand our commitments in this area?

If you look at the data on science, health care and business, when you bring a diverse group of individuals together — diverse ideas, background and experiences — you get better outcomes. Every aspect of that contributes to richer science, better health care and better education. There’s also a moral aspect of including people in conversations who previously haven’t been included, including communities who perhaps have not been offered the same opportunities.

To me, bringing together what’s right with what we know works is an important component of how I think about diversity. I think at a place like Weill Cornell Medicine, we should lead and we should not be shy to do so.

How can academic medical centers address challenges that bear upon its pipeline of future physicians and their well-being — including the shortage of doctors, the need to increase representation of historically underrepresented people in STEM, and burnout — during medical education and training?

As we’re thinking about a more diverse scientific and medical workforce, we have to be thinking about and investing in the pipeline, and you can almost not be too early.

And you can’t just get people here, you have to support them. This is another area where a lot more work needs to be done. I understand the pressures of the electronic medical record — the joy that it’s given us in terms of being able to access information, but the burden it’s given us is being the people who input information. A place like Weill Cornell Medicine, with access to great engineers and great computer scientists, should be at the forefront of helping to figure that out because technology is both part of the issue and can be part of the solution.

We also have to think about different paradigms of training, different ways of thinking about work hours, workforce and more team-based care.