“Every person who is overweight carries a lot of extra anxiety. Some of it justified, some of it just your own perception.”

Science Over Stigma

Features

By probing the physical cause of obesity, researchers have repudiated harmful misconceptions about the condition, leading to new, highly effective medications.

At 55, Audrey Friel has spent much of her life trying to shed pounds from a body determined to keep them. She has tried brand name liquid, carb-cutting and points-based diets, as well as fads centered on plain slices of deli meat or foul-smelling, cabbage-based soup. Any weight she lost returned in time, and her body increased its resistance to each subsequent attempt. But more than the scale, Friel struggled with the stigma that came with her size.

She remembers visits from the endocrinologist treating her diabetes while she was hospitalized before the premature birth of her son in 2004. “He would come into the room, and he would say,” — her voice drops, mimicking his disapproval — “‘pancakes? You’re supposed to get eggs.’”

For emotional support, she wanted her husband, Don, in the room when the endocrinologist arrived. “I was panicking in a hospital bed trying to hold in a baby and feeling the dread of knowing he was going to come in and judge me,” says Friel, who lives with her husband in New Jersey.

Don Friel, 54, has struggled with his weight, too, on two occasions losing, then regaining, at least 100 pounds. He was hired as a second-grade teacher during a thin phase. Later, his weight spiraled up to 350 pounds, and he wondered: “Would I have gotten the same job at this weight?”

“Every person who is overweight carries a lot of extra anxiety,” he says. “Some of it justified, some of it just your own perception.”

A Physical Condition

The problem, says the Friels’ physician, Dr. Louis Aronne — director of the Comprehensive Weight Control Center, the Sanford I. Weill Professor of Metabolic Research, and a professor of clinical medicine — is that many people, even some physicians, don’t understand obesity.

“It looks like it’s so easy to treat, just eat less and exercise more, right?” he says, echoing the misconception at the source of a great deal of misery. “Here’s a physical characteristic people are criticized for, and that only adds to the difficulty.”

Science agrees. Research has demonstrated, Dr. Aronne notes, that obesity is a physical condition, one associated with other serious health problems, but not a reflection of a person’s willpower or character. Rather, he points out, decades of studies say the stubborn excess weight results from disruptions to the complex internal system that regulates body weight.

Dr. Aronne has sought to apply this scientific understanding to the practice of medicine and, at the same time, bring obesity treatment into mainstream health care. Clinical trials he and other Weill Cornell Medicine investigators conducted helped to shepherd in tirzepatide (marketed as Mounjaro and Zepbound). This medication, along with another type of injectable, semaglutide (Wegovy and Ozempic), have proven highly effective for weight loss and managing a related condition, diabetes.

In Dr. Aronne’s office, the Friels at last found a judgment-free zone. “Gain, lose, his attitude toward you as a patient is the same,” Don Friel says.

Two Missing Molecules and a Setpoint

Shortly after joining Weill Cornell Medicine’s faculty in 1986, Dr. Aronne first encountered then cutting-edge research into the biological basis of obesity when he began visiting The Rockefeller University lab of Dr. Rudolph Leibel. Dr. Leibel (now a professor of pediatrics and medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons) was hunting for a pair of genes that, when mutated, made mice obese. If a mouse with mutations in one of the genes received blood from a healthy mouse that presumably contained the factor encoded by the ineffective gene, the mouse lost weight — a result suggesting a circulating factor in the bloodstream might regulate body weight.

The research fascinated Dr. Aronne. “Here was proof that something physical was going on,” he says.

In time, Dr. Leibel and his collaborators demonstrated that the mouse lacked leptin, a hormone secreted by fat cells that stimulates satiety, diminishes appetite and increases the energy the body burns. When it received the hormone through blood, it lost weight.

Leptin, it turns out, is only one component of a weight-regulation system with a built-in redundancy that resists any tampering. Scientists have so far documented eight hormones that contribute. Along with fat tissue, an array of organs — the pancreas, the liver, the stomach and the intestines — secrete these signals, which act on the brain, especially in the hypothalamus region, to stimulate or suppress hunger and to adjust energy expenditure.

Like a programmed thermostat, the hypothalamus seeks to keep body weight in a specific range, or set point. Often in obesity, this weight thermostat is set quite high. If body weight falls below this elevated set point, as it would on a diet, the system reacts as though facing starvation: It recalibrates hormones to stimulate appetite and slows energy expenditure, bringing back the pounds.

The discovery of leptin raised hopes researchers could harness it to promote weight loss in people, not just mice. But the dream of a leptin-based treatment for obesity never materialized. Except for rare cases in which the leptin gene is mutated, most people who carry large amounts of excess weight have elevated levels of leptin, but do not respond properly to it. However, other appetite-regulating hormones, and one in particular known as GLP-1, would later succeed where leptin fell short.

“The impact is larger than any other medication I have encountered since I was a medical student.”

Every Tool in the Toolbox

When Stacy Colonna, now 58, heard someone say they felt full and planned to save part of a meal for later, she used to assume that person was lying.

“I was like, ‘Oh come on, you’re just being disciplined.’ That’s what I had heard my entire life: ‘you’re not disciplined,’” she says, describing the seemingly endless hunger she experienced. “I simply thought everyone was just better at holding it off than I was.”

Colonna, of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, traces the start of her fight with her body back roughly four decades when, as a teenager, she was told she was overweight and sent to “fat camp” for two summers. In her late 20s, she lost weight and kept if off for about a decade, until an unsuccessful attempt at in vitro fertilization pushed her to an all-time high of 270 pounds. She went on to develop diabetes and high blood pressure, two conditions that often accompany obesity. Colonna knew she needed a solution that didn’t rely on self-control.

In 2015, she underwent bariatric surgery, which closes off the lower section of the stomach, creating a small pouch at the top that is attached directly to the lower intestine. Bariatric surgeries typically produce the greatest weight loss but entail more serious risk than weight loss medications.

The immediate results amazed Colonna. Her blood sugar and pressure measurements fell dramatically. And there was more — “for the first time in my life I finally understood that sensation of full,” she says.

But ultimately, it wasn’t enough. Five years later, her weight loss plateaued.

Her physician, Dr. Rekha Kumar, saw a warning sign: Colonna’s hunger had returned, indicating her body was fighting to regain weight. To stay ahead of it, Dr. Kumar began prescribing weight loss medications. Like Dr. Aronne, Dr. Kumar, an associate professor of clinical medicine, typically uses combinations of medications to more effectively interfere with the weight regulation system, along with recommendations on diet and activity. Last September, she added semaglutide to Colonna’s regimen.

Semaglutide mimics the activity of the hormone GLP-1, which is produced by specialized cells in the intestine. Like leptin, GLP-1 travels to the brain and prompts a feeling of satiety. GLP-1 also increases the amount of time food spends in the stomach, further contributing to the feeling of fullness and accompanying loss of appetite. Finally, it stimulates the pancreas to release another hormone, insulin, which prompts the body’s cells to take sugar out of the blood after someone has eaten.

Researchers discovered GLP-1 when studying the body’s system for controlling blood sugar, which overlaps with weight regulation. In 2005, the FDA approved the first drug to mimic GLP-1, exenatide, to treat diabetes. However, exenatide caused more nausea than weight loss, Dr. Aronne says. Over the years, improvements to GLP-1 drugs made them more tolerable and effective for reducing weight. In 2021, the FDA approved semaglutide for weight loss. Tirzepatide, an even newer drug, doubles down, mimicking both GLP-1 and another appetite-suppressing hormone, GIP.

Clinical trials of semaglutide and tirzepatide, some of which were conducted at Weill Cornell Medicine, produced striking results. A multi-institutional study elsewhere described in The New England Journal of Medicine found that, after 68 weeks of injections of semaglutide, people considered overweight or obese lost, on average, 14.9% of their body weight — an unprecedented result for a weight loss medication at the time. A more recent trial reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association and led by Dr. Aronne showed tirzepatide could go even further. After 88 weeks, participants lost, on average, just over 25% of their body weight.

Semaglutide gave Colonna another new experience, this time of silence. The new medication shut down a constantly chattering voice in her head, which had followed her through life obsessing about what she should eat, what she wanted to eat and how to get it. “I can most closely analogize it to smoking,” she says. “It was just on and on about food — [then] gone.”

She’s now down to the weight she maintained through much of her 30s and quick to note that medications and surgery were only part of the solution. She also exercises with a trainer, sees a therapist and has changed her diet and relationship with eating.

“You use every tool in the toolbox available to you,” she says.

A Condition with Company

Obesity often overlaps with and can cause other serious health conditions, notably diabetes. In this disease, the body loses its ability to properly control the amount of sugar circulating in the blood. Over time, elevated sugar exacts damage on tissue that can lead to debilitating, even deadly complications. Physicians use both semaglutide and tirzepatide, which suppress appetite and lowers blood sugar, to treat diabetes and stave off these ill effects.

“The impact is larger than any other medication I have encountered since I was a medical student,” says endocrinologist Dr. Laura Alonso, chief of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism and director of the Joan & Sanford I. Weill Center for Metabolic Health, who prescribes these medications to her diabetic patients. “They’re just extraordinarily effective.”

She predicts their widespread use could lead, over the next decade, to a marked reduction in diabetes complications such as heart disease, stroke, loss of eyesight, kidney failure and nerve dysfunction. Meanwhile, by effectively treating obesity, these drugs could also significantly decrease the conditions that can accompany it, such as arthritis and certain cancers.

Treating patients earlier with the medications, physicians say, could amplify their potentially enormous benefits.

“People with prediabetes” — when blood sugar is elevated, but not yet at diabetic levels — “are accumulating risk for complications,” says Dr. Alonso, the E. Hugh Luckey Distinguished Professor in Medicine and a professor of medicine. “We could change the trajectory of their health.”

Likewise, Dr. Aronne predicts that, in the future, physicians will use medications like semaglutide and tirzepatide sooner and in smaller doses to treat people who are overweight to prevent them from progressing to obesity. A BMI of 30 or more is generally considered obese.

“I don’t think we completely know all of the things that dysfunction in obesity, but something is different in the past 40 years.”

Hurdles, Medical and Financial

For all the good they can do, these medications can still come with major drawbacks. First off, they simply don’t work for everyone, and those who use them successfully must continue taking them indefinitely to maintain the benefits. What’s more, semaglutide and tirzepatide can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other unpleasantness. And it’s important that those who take them work to maintain strength and muscle mass, according to Dr. Alonso.

“When people lose weight by just restricting their food intake, they lose fat, but they also lose muscle and bone,” she says. “So even the success story of weight loss and diabetes control may come at a cost.”

This issue, she says, needs further investigation and will likely be among those taken up by the new clinical arm of Weill Cornell Medicine’s Friedman Center for Nutrition & Inflammation, which is directed by Dr. David Artis. Dr. Alonso will serve as interim co-director of the clinical program, which is backed by a recent $9 million gift from the Friedman Family Foundation.

Yet even with these caveats, the biggest challenges for use of the drugs may be financial.

Not everyone who needs the medications can afford to take them. Semaglutide and tirzepatide can cost more than $1,000 per month out of pocket. Many insurers, including Medicare, the federal insurance program for people 65 and older, don’t cover them.

What’s more, while these drugs can be invaluable for individuals, they don’t solve the problem at the heart of rising rates of obesity.

Once a relatively rare condition, obesity has become much more common, both in the United States and globally.

In 1960, obesity affected about 13% of U.S. adults 20–74 years old. In data from 2017 through 2020, the obesity rate for all adults over 20 grew to nearly 42%, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Globally, adult obesity rates have nearly tripled to about 13% in 2016, according to the World Health Organization.

In addition to sedentary lifestyles and ready access to calorie-rich food, researchers have explored an array of other potential contributors. These include increased exposure to chemicals, such as those in flame retardants and pesticides, that mimic the effects of hormones in the body; people sleeping less; inheritable changes in how genes are regulated; certain infections; and changes to gut microbial communities.

“I don’t think we completely know all of the things that dysfunction in obesity,” Dr. Kumar says. “But something is different in the past 40 years.”

A Shift in Attitude

Within the scope of what they can accomplish, however, weight loss medications will likely continue to improve, according to Dr. Aronne. He and his colleagues are, for example, currently testing a combination of semaglutide and a substance, cagrilintide, that mimics another satiety-inducing hormone, amylin. In another trial, they are studying orforglipron, a new GLP-1 drug formulated as a pill, that could be less expensive to produce than the oral form of semaglutide now available.

Since he began seeing Dr. Aronne in 2012, Don Friel is down 140 pounds from his peak weight.

His body fights the medication, however, and to keep the weight off, he increased his dosage of semaglutide.

“When I start getting hungry,” he says, “I get a little nervous, because” — “it’s a lifelong feeling,” Audrey Friel interjects.

“Yeah,” Don Friel says. “I just don’t want to go back.”

The liver disease that Audrey Friel had long experienced became life-threatening in 2019, leading to a transplant two years later and dramatic fluctuations in her weight. When she was young, she used to say she didn’t care if she was healthy, she just needed to be skinny. She no longer feels that way.

At present, she’s taking tirzepatide, among other medications. Her weight is down about 85 pounds from her high, to a point where she can fit into her clothes and do what she wants to do. She’s still losing, but she doesn’t have a goal, or a need, to be thinner.

“I am still not skinny by any means, but it doesn’t bother me,” she says. “I don’t have any worries about my weight holding me back.”

Dr. Louis Aronne serves as a paid advisory board member for Eli Lilly and Company and Novo Nordisk.

Summer 2024 Front to Back

-

Features

Science Over Stigma

By probing the physical cause of obesity, researchers have repudiated harmful misconceptions, leading to new, highly effective medications. -

Features

The Sounds of Science

How insights from ornithology, coupled with advances in AI, could enable doctors to screen for disease using the human voice. -

Features

Bones’ Secret Cells

Research led by Dr. Matthew Greenblatt and his lab is revealing connections between bone stem cells and a surprising array of conditions — including cancer. -

Notable

Expansion in Midtown

A 216,000 square-foot expansion of clinical and research programs at 575 Lexington Ave. will provide state-of-the-art clinical care at the Midtown Manhattan location. -

Notable

A Dramatic Growth in Research

In the decade since the Belfer Research Building’s opening, Weill Cornell Medicine’s sponsored research funding has more than doubled. -

Notable

Dateline

Heart disease presents differently in resource-poor countries like Haiti. Dr. Molly McNairy and colleagues are working to identify underlying causes and prevention. -

Notable

Overheard

Weill Cornell Medicine faculty members are leading the conversation about important health issues across the country and around the world. -

Notable

News Briefs

Notable faculty appointments, honors, awards and more — from around campus and beyond. -

Grand Rounds

Living With Endometriosis: A 12-Year Journey

How the right treatment reduced the pain of endometriosis -

Grand Rounds

Taking Action Against Lung Cancer

Monitoring by Weill Cornell Medicine’s Incidental Lung Nodule Surveillance Program can lead to early cancer detection. -

Grand Rounds

News Briefs

The latest on teaching, learning and patient-centered care. -

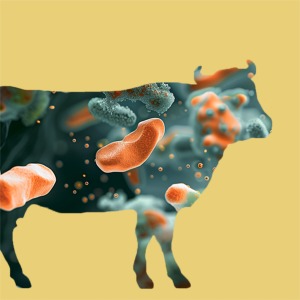

Discovery

Gut Check

New evidence shows that a bacterium found in the gut of livestock could be a trigger of multiple sclerosis in humans. -

Discovery

Researchers Chart the Contents of Human Bone Marrow

A new method for mapping the location and spatial features of blood-forming cells within human bone marrow provide a powerful new means to study diseases that affect it. -

Discovery

Findings

The latest advances in faculty research, published in the world’s leading journals. -

Alumni

Profiles

Forging critical connections to move research from the bench to the bedside, our alumni are making an impact. -

Alumni

Notes

What’s new with you? Keep your classmates up to date on all your latest achievements with an Alumni Note. -

Alumni

In Memoriam

Marking the passing of our faculty and alumni. -

Alumni

Moments

Marking celebratory events in the lives of our students, including the White Coat Ceremony and receptions for new students. -

Second Opinion

Equal Risk

Does race have a role in calculations of health risks? -

Exchange

Health Equity

Two faculty members discuss the importance of community-engaged research in their work to help combat cancer disparities fueled by persistent poverty. -

Muse

Finding Strength in Art

Surin Lee is a Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar medical student, Class of 2026, and a visual artist. -

Spotlight

Partners in Solving Surgical Challenges

Dr. Darren Orbach (M.D. ’98, Ph.D.) and Dr. Peter Weinstock (M.D. ’98, Ph.D.) are pioneering the use of practice simulations to ensure successful complex surgeries.