“Having a sensory deficit like hearing loss can be really hard, disorienting and frightening, which can definitely affect mental health,” he says. “Having gone through this experience helps me have more patience and empathy for my patients and strengthens our therapeutic alliance.”

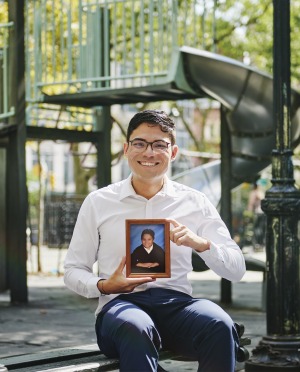

Dr. Camelo’s dream of becoming a doctor was sparked by his family’s frequent medical appointments for a younger sibling who was born with serious health issues. He found himself inspired by knowledgeable and caring doctors and fascinated by the hospital setting.

“Even at 6 years old, I started thinking that this was something I wanted to do,” he says.

But he began having doubts about this plan just a few years later. At 10, Dr. Camelo abruptly lost hearing in his left ear. Doctors soon told him that his hearing loss was permanent, and its type — known as sensorineural — couldn’t be helped by hearing aids. Because CIs at that time were approved only for individuals with bilateral hearing loss, there were no options to improve his hearing.

Resigned to a life with one working ear, Dr. Camelo made his own accommodations: sitting close to teachers at school, chatting with friends at his right side, learning to lip read. He worked hard, excelled in academics and got accepted to Johns Hopkins University for his undergraduate degree. After initially considering a career in research rather than medicine — a better fit, he thought, for a life with hearing loss — he gradually felt more and more confident that he’d be able to succeed as a doctor.

Acceptance to Weill Cornell Medicine in 2020 made his path feel more certain. But doubt crept in again as he began medical school at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Universal masking requirements made lip reading impossible, stymieing his interactions.

“I noticed myself really struggling to connect with my classmates, professors and patients,” he says.

After a referral to Dr. Samuel Selesnick, Dr. Camelo learned that CIs had been approved for patients like him in 2019. Nervous but excited, he scheduled his implant surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell for January 2021. Three weeks later, he met with his audiologist, Haley Bruce, to activate his device.

“We call that visit the ‘hearing birthday’ for cochlear implant recipients. It’s always an emotional appointment,” she says.

There’s a common misconception that patients can understand speech perfectly as soon as the device is turned on for the first time, explains Bruce. However, activation is just the beginning of a new chapter. Like all CI recipients, Dr. Camelo needed countless hours of aural rehabilitation with speech-language pathologists and numerous programming adjustments to the cochlear implant. This aftercare not only took a toll on Dr. Camelo’s busy medical school schedule, he says, but also on his energy. After long days in the classroom and the clinic, the focus required to learn how to interpret the unfamiliar sounds emanating from his new CI was draining.

Over time, however, the work paid off. In July, Dr. Camelo began his psychiatry residency at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell. In the future, he plans to focus on geriatric patients, a population that has a high rate of hearing loss.

“I don’t know if I would have been able to go into psychiatry without my CI,” he says. “With my experience, I feel better equipped to help a vulnerable population. I’m really looking forward to it.”